A last will and testament may not seem as valuable as, say, family heirlooms like silver. But it’s crucial for everyone involved: the person making the will and those who inherit, as well as for historians later on. While inventories list possessions in detail soon after someone dies, wills show relationships, friendships, and care among the things being passed down. They give us insight into what mattered to people in the past and preserve glimpses of lives that might otherwise be forgotten. Don’t assume that the formal style of a will means it can’t also reveal individuality. In fact, sticking to conventions might highlight how unique some people’s choices and words were.

In early modern England, wills from places like Essex follow a similar structure. They start with the date, place, name, and job of the person making the will, along with a statement that they’re in good health and sound mind to write or dictate the document. The testator might also mention their Protestant beliefs, emphasizing salvation through Christ rather than through saints. Then, they divide up their real estate (land and property) and personal estate (money and belongings).

These documents usually follow a set order: first, they mention who gets the land and property, then the money, and finally the “goods,” which can include household items like furniture, kitchen stuff, jewelry, clothes, and animals (though pets weren’t seen as property back then, so they weren’t mentioned in wills). At the end, there’s a general statement to cover anything else: “all the rest of my stuff goes to my executor.” Then, the testator signs it (with their name or a mark) and so do witnesses.

Even though wills can seem standard, historians can find unique info in them. For example, who the witnesses are and who gets what can reveal connections between neighbors. And the types of things left to different people can show more about the society back then. For instance, wills from Essex in the early 1600s showed that women were more likely to inherit poultry and pigs than men, but only 40% of horses went to women. This tells us about the roles of men and women in rural areas: women mostly worked around the house and yard, so they got the animals used there.

In addition to showing who owned what, wills sometimes give us a peek into the emotions of the person making the will. Alongside loving gifts, we might see signs of strained family relationships. For example, in his will from 1628, Robert Salmon of Broxted said his daughter Mary would lose her inheritance if she married without her mother’s approval. Similarly, John Birche of Hatfield Peverill left his unkind wife Mary just one shilling and sixpence, saying she caused him a lot of trouble and grief. Joan Games of Little Bentley only gave her rebellious son George five shillings in her will six years later. But we also see acts of kindness and neighborliness. In 1630, John Kitto of Ulting left money to Deniss Trolope and Susan Walters for taking good care of him when he was sick.

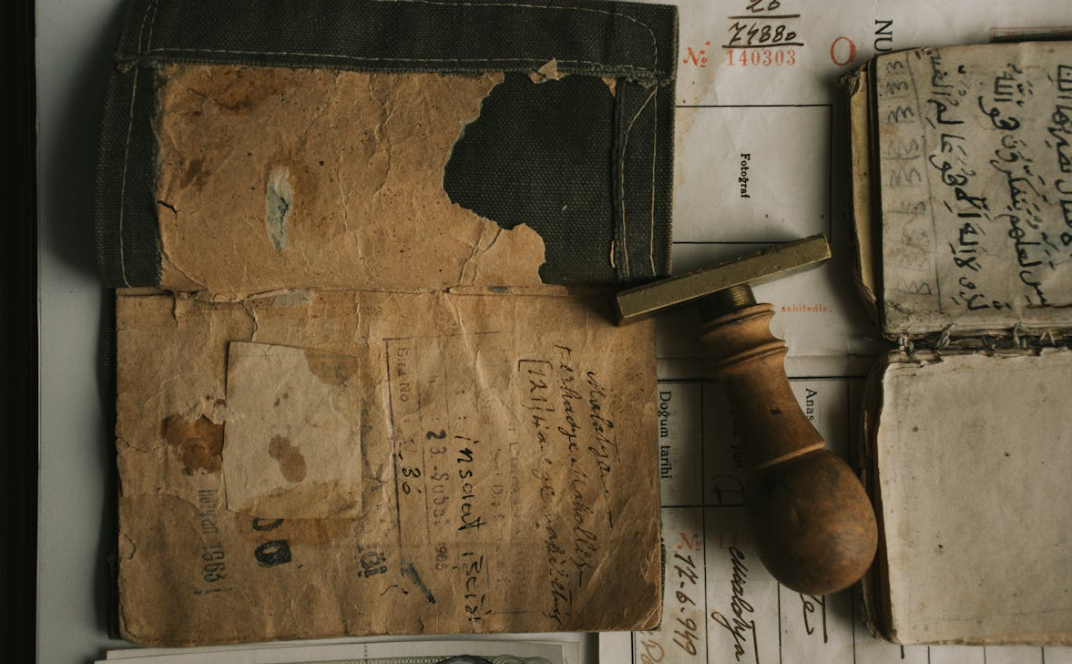

Besides showing us what people left behind, wills themselves are important historical artifacts. It’s not just the contents that matter, but also their physical form. For example, some wills are written on expensive parchment instead of paper, which can tell us something about the person who made it. The handwriting can also give clues. Some wills are neatly written by someone with good handwriting, while others are hard to read, showing that the person making the will may have been poor and not had access to someone who could write well. Even though they might not have much, what they did have was important to them.

Wills also tell us about widows. Even though they usually didn’t inherit land, their wills could still be long, with lots of small items left to family and neighbors. This shows us the communities of women that might not be visible in other documents.

So, it’s logical for historians to see wills as records of cherished items. But they’re valuable in another way too: they give us a glimpse into lives that would otherwise be forgotten, and they’re important as physical objects too. If we were to scan them and then throw away the originals, as the Ministry of Justice suggested for wills made after 1858, we’d be losing something irreplaceable for future historians.