In this series, we’ve been talking about how some people have used the idea of a “white, racially pure Middle Ages” for their own political reasons, especially by right-wing extremists. But it’s not just extremists who believe in this idea. Many people, maybe most, learn about the Middle Ages from movies, TV shows, and video games, rather than from school or books by experts. And in these popular versions of the Middle Ages, almost everyone is white. Even in fantasy stories like Game of Thrones or Dragon Age, they often explain the lack of diversity by saying there were no people of color in Europe during the Middle Ages.

But where did this idea come from? Where did these images of the medieval past originate? How did people start thinking of the Middle Ages as being all about white people? To understand this, we need to go back to the time when our ideas about race and the Middle Ages first started to develop: the 18th century.

Making “Race”

In Paul Sturtevant’s article “Is Race Real?”, he explains that the idea of “race” is something people made up over time, so it has a history. Most histories of race and identities like “whiteness” focus on key thinkers and intellectual circles where these ideas started.

The idea of a “white” race began during the Enlightenment in the 18th century. Carl Linnaeus was one of the first to classify humans into races in his book Systema Naturae in 1738. By 1758, he added more descriptions about physical and social traits. He described Europeans as “white-skinned” and organized by laws. In the late 18th century, people were debating about the differences—both physical and cultural—between different groups of people.

It’s not surprising that European thinkers always thought of themselves as the best in these debates.

Making “Race” Popular

Even though modern science has shown that race is not real, racism still has a strong influence. Social theorists Michael Omi and Howard Winant say that debates about race can have big effects on societies. So, it’s important to understand how ideas about race and white superiority spread among regular people.

Oliver Goldsmith, known for writing The Vicar of Wakefield, helped popularize the idea of whiteness in Britain and its colonies with his book A History of Earth and Animated Nature in 1774. He translated and adapted ideas from Linnaeus and other early biologists.

Goldsmith didn’t believe races were totally different, like many of his peers did. But he still thought Europeans were the best of humanity. He wrote:

They [those variations] are actual marks of degeneracy in the human form; and we may consider the European figure and colour as standards to which to refer all other varieties.

He also said that being white was the best because it looked the most beautiful and showed emotions better, and that Europeans looked more like God than other people.

Even though Goldsmith mainly translated other people’s ideas and didn’t add much new to the discussion about race, he’s important because he made those ideas easy for many people to understand. A History of Earth and Animated Nature was one of many books that helped spread biological writings and the idea of race. It was reprinted many times in the UK and America during the 19th century, and in one American edition, the chapter on race was moved to the start of the book, showing how important the publisher thought it was.

Hannah Arendt says that in English thinking, race came about because people wanted to give noble standards to everyone. In the 18th century, democracy, freedom, and equality were important ideas during the French and American Revolutions. Race allowed Europeans and European settlers in places like America to make a system where they were seen as better than others.

Once “race” became popular and accepted, white people had a whole system of science saying they were better. This was important because it became part of new national economies and global trade, like slavery, taking land from indigenous people in settler colonies, and taking resources from around the world by European powers.

Making “Race” Medieval

But why are we talking about the Middle Ages in all of this? In the 18th century, people started thinking that humans were divided into different racial groups, each with their own physical, cultural, and social traits passed down from their ancestors. This meant that history had to be looked at in a new way. European countries needed new stories about where they came from that fit into this racial idea.

Classical Greece and Rome were seen as the best civilizations. But countries like England and France, who couldn’t trace their ancestry back to those places, needed a new source for their identity. They found it in the Middle Ages, even though, according to the thinking at the time, those were the people who destroyed Rome. We still think of the Middle Ages as barbaric, but since the 1760s, Western countries have found things to be proud of in that time, even if they don’t deserve it. Racial origins are part of that pride.

There were levels of importance even among white people, who were seen as the best in the world. European countries competed to grow their empires worldwide and discussed racial differences among themselves. They looked at where their ancestors came from to explain why some nations succeeded while others didn’t. The debates about which nations had the same ancestors and whose ancestors were better helped create the modern idea of whiteness.

Making “Race” Linguistic

Studying the history of languages made people realize they were connected to other nations, even if they hadn’t thought about it before. Language, which is cultural, became a sign of being related racially.

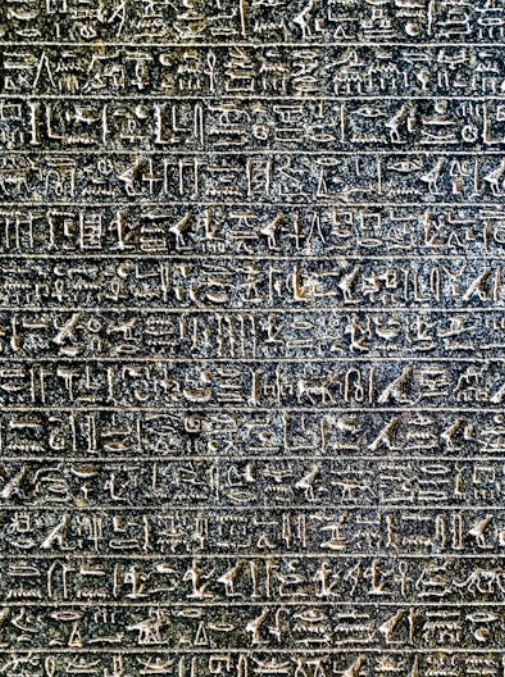

Because of this, people became more interested in the Middle Ages. Medieval manuscripts were often the oldest written records of a language and could be used as evidence in these discussions. The Middle Ages also gave us the earliest historical writings by people about their own country, like English people writing about England.

The whitewashing of the Middle Ages mostly happened in discussions within Europe, rather than in writings about races globally, at least at first. One example is seen in the writings of Goldsmith’s friend, Thomas Percy. Percy strongly believed that the English, Scandinavians, and Germans came from the same “Gothic” race, while the Irish, Scots, and French (among others) came from a “Celtic” race.

Even though people don’t remember him much now, his studies of the Middle Ages were really popular and influential back then. His first book, Five Pieces of Runic Verse Translated from the Icelandic Language (1763), argued that English, Scandinavian, and German languages were closely related.

His most famous book was Reliques of Ancient English Poetry (1765), a three-volume collection of supposed medieval ballads. Many of these were actually from the early modern period, not medieval, and Percy changed them a lot to make them more interesting to readers. Each volume had an essay saying the poems were part of English culture. Some of his ideas were questioned, but the book was so popular that he released a second edition in 1767. In this new version, he argued that Saxons, Vikings, and Normans were all part of the same “Gothic” group, so modern English people could see themselves as racially pure.

Percy’s last book about the Middle Ages was Northern Antiquities (1770), where he translated Paul-Henri Mallet’s work. Mallet mixed up the Celts and Goths in a history of Denmark that many people read. Percy started translating this book in the early 1760s and was determined to show that the Goths and Celts were different races. In a letter in 1764, he said Mallet’s book was a mistake, and he wanted to fix it in his translation. When his translation was finally published, he added lots of notes and a whole Preface to prove they were racially different. He used history, language, and science to back up his idea.

All three of Percy’s books about the Middle Ages were meant to make readers at the time feel connected to that time period because of their race. The medieval poems in the books gave readers something they could touch to connect the idea of race and identity.

Making “Race” Popular Cultural

Reliques was so liked that Percy’s books had four editions during his life. The famous author Sir Walter Scott, known for books like Ivanhoe and Waverly, loved them. Because of these books, famous English Romantic poets like William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge started writing in a simpler style, like they thought people did in the Middle Ages. Important German Romantic writers like Johann Gottfried von Herder, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and the brothers Grimm, who wrote fairy tales, were also influenced by Percy’s ideas.

Reliques was reprinted many times in the 19th and 20th centuries. There were cheap versions, fancy ones, and even ones for kids. A book from the 19th century praised Percy for showing the differences between Celtic and Teutonic races.

Percy spent a lot of time trying to prove that these races were different, using the Middle Ages as proof. He did what Omi and Winant call “making up people.” His books made medieval stuff something English people could be proud of because it was part of their race. They changed how English people saw themselves, making race and the Middle Ages important. Other writers and historians across Europe copied his style, inspired by reading his books.

Percy and Goldsmith were just two of many who linked whiteness to the Middle Ages. In the 1760s, there was a big increase in interest in the Middle Ages across Europe. Architecture, art, and literature started to focus more on medieval themes. This interest often went along with nationalist thinking.

Once people accepted the idea of race, they saw the European Middle Ages as a place only for white people. In stories like Sir Walter Scott’s novels, you rarely see people of color. They might show up as enemies in stories about crusaders, but they’re not part of the white Christian societies of medieval Europe.

Writers like Scott and later ones, like J.R.R. Tolkien, used race-based nationalism to connect medieval Europe to white European nations. As I argue in my recent book Race and Popular Fantasy Literature: Habits of Whiteness, the ways that early popular culture talked about the Middle Ages have influenced how we think about them today in western culture.

Making “Race” Academic

It’s not just made-up stories about the Middle Ages that make them seem like places only for white people. Even academic subjects have been shaped by race. In the 18th century, there weren’t any English departments in universities. It wasn’t until the 19th century that the study of old languages like Old Norse and Old English became part of academic disciplines. The way these subjects were set up had a racial aspect, and many are still set up this way today. For example, when I started studying in an English department, we learned Old Norse and Old English alongside Middle English and modern literature. We didn’t learn Old French, even though French had a big influence on English because of the Norman Conquest. We also didn’t learn Medieval Spanish or Middle Arabic. This is how a lot of English departments are organized in English-speaking countries.

This goes back to theories like Percy’s, which said that Old Norse belonged to English speakers because they shared a made-up Gothic racial ancestry. French and Spanish, which are from a different family of languages called Romance, weren’t included. Arabic definitely wasn’t. The idea that English literature is separate from other languages’ literature comes from these race-based ideas in philology.

People who believed in racial ideas thought that Celts, Goths, and others in Europe were all part of the same group, called homo europaeus, because they had a shared Middle Ages. To make their race seem different, their history needed to seem different too. So, things we think of as unique to the Middle Ages, like knights, castles, and feudalism, were only thought to be in European history. Anything similar found in other cultures was ignored or dismissed. That’s why for centuries, “medieval” meant “white.”

Undoing the Damage

The idea of the Middle Ages being only for white people is being challenged now. In popular culture, we see actors of color taking on medieval roles, like Angle Coulby as Gwen in the TV show Merlin, and Idris Elba as Heimdall in Marvel’s Thor movies. Websites like “People of Colour in European Art History” are breaking down the idea that only white people were part of the Middle Ages. Scholars are also studying the Global Middle Ages, looking at how it was around the world. And ideas about language and race are changing, with more focus on speaking multiple languages and breaking down borders between countries.

We need to keep pushing for change. We should ask scholars and creators to give us new views of the Middle Ages that aren’t stuck in old racist ideas from the 1700s and 1800s. The Middle Ages were made white back then, but they don’t have to stay that way.