“A person is considered foolish if they write a secret without hiding it from others,” wrote philosopher Roger Bacon in the 13th century. Throughout history, leaders, soldiers, and even lovers have used secret codes to keep their messages safe. According to Mark Frary, the author of The Story of Codes, the main goal of using codes and ciphers has always been the same: to send messages in a way that enemies can’t understand them.

In ancient Greece, messengers would have messages tattooed on their shaved heads until their hair grew back. This was a slow method, but it served the same purpose as encrypting messages with machines like Germany’s Enigma during World War II. In the early days of the telegraph, businessmen used codes to hide information about prices and orders. Nowadays, encryption keeps online financial transactions secure. Throughout history, famous people like Julius Caesar and Thomas Jefferson used ciphers, and some systems, like the Masonic Cipher, have been around for hundreds of years. Here are eight famous ciphers that have had a big impact on the world.

Scytale

The Spartans had a simple but clever way to send secret messages: the scytale. It was a wooden rod that they wrapped with strips of parchment where they wrote their message. When the parchment was unwrapped, the message couldn’t be read. But when it was wrapped back around another scytale of the same size, the message became clear.

Plutarch, a writer from ancient times, explained how the Spartans used the scytale:

“They made two round pieces of wood that were the same size, and they gave one to their messenger while keeping the other. When they wanted to send a secret message, they wrapped parchment around their scytale. The messenger would then wrap the parchment around his own scytale and read the message.”

But once someone knew the size of the scytale, it was easy to figure out the message. So, this method was only good for short messages.

Caesar Cipher

Caesar Ciphers are a way to change letters in a message by shifting them a certain number of spots in the alphabet. Julius Caesar, a Roman general, used this method to hide his messages when he was away fighting battles in Gaul. According to the Roman writer Suetonius, Caesar mixed up the letters so no one could understand the words. If someone wanted to decode it, they had to move each letter back by three spots in the alphabet. For example, they’d change A to D.

Caesar liked using secret codes so much that a writer named Valerius Probus wrote a whole book about his methods around the year A.D. 1. Unfortunately, that book is lost now. But we do have Caesar’s own stories about his wars in Gaul. In one story, he sent a letter to Cicero, who was stuck in a siege. Caesar wrote the letter in Greek instead of Latin to keep the enemy from figuring out his plans. Then, he attached the letter to a spear and threw it into Cicero’s camp. It got stuck in a tower for two days before Cicero found it.

Freemason Cipher/Pigpen Cipher

In the 1700s, Freemasons used the Pigpen Cipher to keep their messages secret. Instead of changing letters, they placed them on a grid and used dots to show which letter was which. This cipher is also called the Masonic Cipher, Napoleon Cipher, and Tic-Tac-Toe Cipher.

“Some people believe it was first used by rabbis to hide messages in Hebrew,” says Frary. The Pigpen Cipher was mentioned as far back as 1531 by a German scholar named Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa in his books about secret knowledge. It was still being used for a long time after that. “Even during the American War of Independence, the British used the Pigpen Cipher,” Frary adds. “It became really popular in the 18th century, especially among Freemasons, which is why it’s also known as the Freemason Cipher.”

Great Cipher of Louis XIV

The Great Cipher was invented by Antoine and Bonaventure Rossignol. Louis XIV used it to send secret messages that stayed secret for 200 years. Instead of using letters, like other ciphers, the Great Cipher used numbers to represent syllables in French. It was more complex because some numbers showed where letters were removed. One decoded message by Étienne Bazeries possibly revealed who the Man in the Iron Mask was.

The Jefferson Wheel Cipher

During the American Revolution, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, John Adams, and James Monroe used secret codes to keep their messages safe. Jefferson even made his own secret codes.

While in France as an American Ambassador, Jefferson came up with the Jefferson Wheel Cipher to outsmart spies who read other people’s mail. It looked like a rolling pin with letters on it. There were 36 discs with letters on each one. The sender would write a normal message but also make a jumbled-up line of letters. They’d send only the jumbled letters to the receiver. When the receiver put those letters into their cipher, they’d see the real message.

In 1802, President Jefferson sent a cipher to Robert R. Livingston, the U.S. Ambassador to France, saying it might be hard to understand but easy to use once they figured it out. He also sent Merriweather Lewis a square table cipher in 1803 to use on his journey with William Clark to explore land for the Louisiana Purchase.

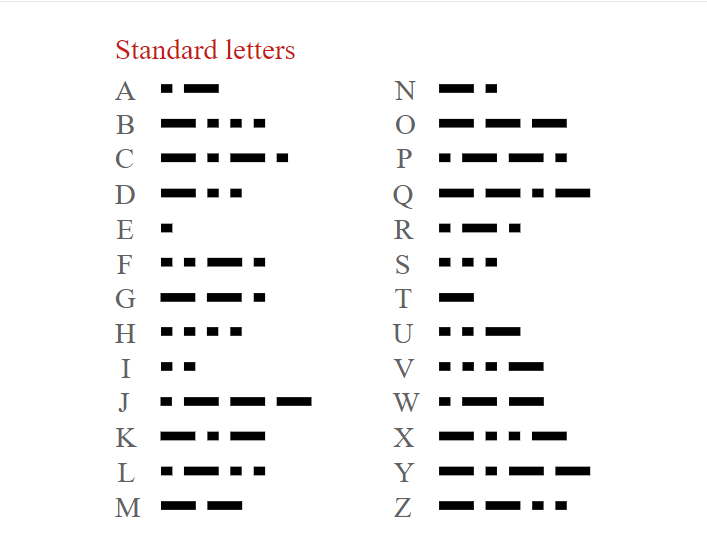

Morse Code

The telegraph, invented in the 19th century, made sending messages over long distances fast. Samuel Morse, an American inventor, created Morse Code. It used dots and dashes instead of letters and numbers. Telegraph workers turned messages into Morse Code and sent them over wires to other stations. There, they were changed back into regular text. But there was a problem: the telegraph wasn’t private. Many people had to know about every message sent.

This privacy issue made people interested in ciphers again. Morse Code was often combined with other encryption methods. First, a message was encrypted using one method. Then it was turned into Morse Code and sent. For example, the American military used the Vigenère cipher from the 15th century. They made their own cipher disks to send secret messages.

The Enigma Code

The Enigma Machine may look like a typewriter, but it was a powerful tool for the German military in World War II. Invented in 1918 for encrypting business info, it became famous during the war for Nazi secret messages. It was portable, fast, and automatic. Text typed into it was encrypted and sent by radio. The receiver used their Enigma machine to decode it.

It was very secure: The machine had scrambler disks with 26 letters (by 1938, each had five disks). Daycode books set the machines to the same settings, changed daily. This made each message have over 150 million million million possible combinations.

“Breaking it manually was almost impossible, but Polish codebreakers did it,” says Frary. “Bletchley Park in the UK then developed mechanical bombes and the Colossus computer for decryption.”

Over 2.5 million messages were decoded by the end of the war. To keep the Enigma Code break secret, the British created a fake spy named “Boniface” as the source of the decoded info.

Navajo Code Talkers

During World War II, the Marine Corps wanted a code nobody could crack. They chose Navajo, a language not well-known outside the Navajo Nation. The 29 Navajo members they hired became “The Navajo Code Talkers,” helping in every Marine operation in the Pacific. The code was key in big wins like the Battle of Iwo Jima.

“Japan’s intelligence chief admitted they broke U.S. Air Force codes but failed with the Navajo code,” says Frary. The code stayed unbroken, and the secret program was only revealed in 1968.

Navajos weren’t the first Native Americans to help the military. In World War I, tribes like the Choctaw used their languages for intelligence.