In the mid-1950s, African Americans wanted to gain equal rights and end discrimination, which they still faced even after slavery ended.

To tackle the segregation, lack of voting rights, and violence against Black people, activists used peaceful protests and disobeyed unfair laws to get public support and change unfair rules.

Here are seven important events in the civil rights movement, including a bus boycott and fights for fair housing.

Nine Black Students Arrive at Central High School in Little Rock

Even after the Supreme Court said schools couldn’t separate Black and white students in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), some Southern states still refused to mix students.

In 1957, the NAACP chose nine Black students to enroll at Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, to challenge these unfair policies. But when they tried to start school, a big crowd of angry white people and 250 soldiers from the Arkansas National Guard, sent by Governor Orval Faubus, blocked them from entering.

After a few weeks of tension, President Dwight Eisenhower made an order that put the state National Guard under federal control and sent U.S. soldiers to make sure the students could go to school. With soldiers from the 101st Airborne Division, the “Little Rock Nine” finally went to Central High, even though they still faced violence and insults while they were there.

The news of what happened in Little Rock was shown on TV and in newspapers all over the world, showing how serious the issue of school separation was and how the fight for equal rights was growing stronger.

Rosa Parks Refuses to Give Up Her Seat

Before Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a Montgomery, Alabama bus on December 1, 1955, Black activists had already been fighting against bus segregation. But when Parks got arrested for standing up for herself, Martin Luther King Jr. and the Montgomery Improvement Association led most of the city’s Black residents to boycott the buses.

Even though city officials and white people tried to stop them, the boycotters didn’t give up. They organized rides and walked long distances to work every day instead of taking the bus.

In June 1956, a court ruled that Alabama’s bus segregation was against the Constitution; the Supreme Court agreed in November. After 382 days, King decided to end the boycott on December 20, 1956. He said, “It’s better to walk with dignity than to ride in shame.”

The boycott’s success showed that peaceful protest could work. It led to the formation of a new group, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, with King as its leader.

The Greensboro Four Sit at a Woolworth Lunch Counter

On February 1, 1960, four Black students at the Agricultural and Technical College of North Carolina went to a Woolworth’s store in Greensboro, N.C. They sat at a lunch counter meant for white people and refused to leave when they were told they couldn’t eat there.

They stayed there until the store closed. The next day, they came back with about 20 other Black students. By the end of the week, hundreds more had joined them. Because of media coverage, news about the actions of the “Greensboro Four” spread fast. This led to more sit-ins happening in other cities across the country, organized by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

Because of these protests, restaurants in the South had to let Black people eat there too. By July 1960, even the Woolworth’s lunch counter in Greensboro was open to everyone. Just like the bus boycott in Montgomery, the sit-in movement showed how peaceful protests could make a big difference in the civil rights movement.

The Freedom Riders Travel South

After the U.S. Supreme Court said segregation on interstate buses was not allowed in 1946, activists from groups like the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and the Fellowship of Reconciliation tested this by taking interracial bus rides through the upper South. This was called the Journey of Reconciliation.

In 1960, when the Court said segregation should also be banned in bus terminals and other places, CORE decided to do more Freedom Rides to check if states followed these rules.

On May 4, 1961, seven Black and white activists got on two buses from Washington, D.C. to New Orleans. As they went further south, they faced more violence. The worst was on May 14, when a big crowd in Anniston, Alabama, attacked them. One bus was set on fire, and the riders were beaten up by the crowd, which included Ku Klux Klan members allowed by the police to attack without getting arrested.

More Freedom Riders kept going. Even when hundreds were arrested in the South, news about how they were treated made more people support their cause. By the fall of 1961, the Interstate Commerce Commission made rules to enforce the Court’s decision against segregation on interstate buses, terminals, and other places.

The March on Washington Showcases Support for Civil Rights

A. Philip Randolph, who started the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, wanted a march on Washington in 1941 to ask for jobs for African Americans during the war. They canceled the plan after President Franklin D. Roosevelt said he would make a rule stopping discrimination in defense industries.

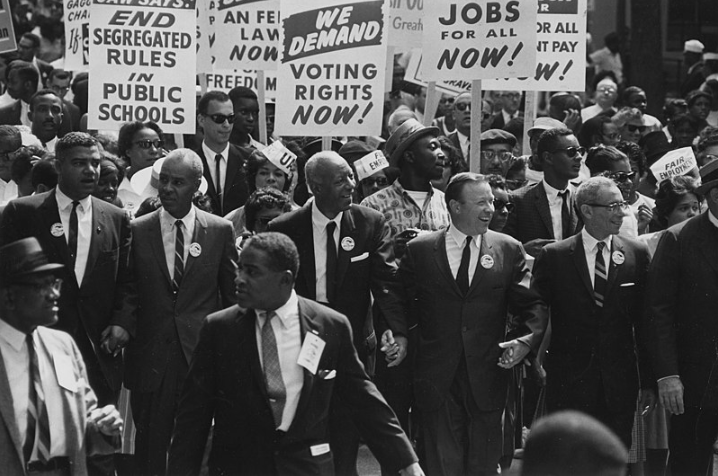

Twenty years later, President John F. Kennedy was trying to make new laws for civil rights, but it was stuck in Congress. Randolph and other leaders wanted to march to make things move faster.

On August 28, 1963, about 250,000 people walked from the Washington Monument to the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. They were showing they were together and supported the civil rights law. Besides talks by Randolph and others, the crowd enjoyed music by famous singers like Mahalia Jackson, Bob Dylan, and Joan Baez.

The last speaker was King, who gave a 16-minute speech that became one of the most famous ever. After the march, King and others met with Kennedy and Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson at the White House to talk about getting both parties to agree on the civil rights law. Even though Kennedy was killed that November, Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 into law less than a year after the March on Washington.

Police Beat Protestors in Selma on ‘Bloody Sunday’

Even after the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Black people in the South still faced problems trying to vote. In early 1965, King and other leaders focused on Selma, Alabama, where very few Black people were allowed to vote.

When a young protestor, Jimmie Lee Jackson, was killed by a state trooper, they planned a march from Selma to Montgomery, the state capital.

On March 7, state troopers attacked the marchers on the Edmund Pettis Bridge, injuring many of them. The violence, shown on TV, made people around the world sympathize with the marchers. President Johnson sent in the National Guard to protect them.

On March 21, thousands of marchers left Selma for Montgomery. When they arrived on March 25, King gave another famous speech at the state capitol. Less than five months later, Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965, giving all African Americans the right to vote.

MLK Joins Marches for Fair Housing in Chicago

By the mid-1960s, even though the Supreme Court said it was illegal to keep Black people out of certain parts of cities, racial discrimination in housing was still common all over the country.

King saw that unfair housing was a big part of the racial problems in the U.S. So, he led the Chicago Freedom Movement in 1965, which called for equal housing rights. In August 1966, the movement had two big wins. The Chicago Housing Authority agreed to build public housing in mostly white areas, and the Mortgage Bankers Association promised to stop unfair lending practices.

King was assassinated on April 4, 1968, in Memphis, with a new fair housing law still stuck in Congress. But just one week later, Congress passed the Fair Housing Act in honor of King. It became one of the last big achievements of the civil rights movement.

This law made it illegal to discriminate against people buying or renting homes based on things like race, religion, or where they’re from. Sellers, landlords, and banks couldn’t refuse to sell, rent, or give loans for housing because of these reasons.